So here we are at the dawn of 2015. At least it was the dawn of 2015 when I started penning this entry. Welcome to the least updated blog in history! Usually the turn of the year is spent at home, full of food, and trying to dodge landing on Park Lane with a hotel while my sister gradually relieves me of all of my hard-earned properties. This year at midnight I found myself unloading cargo and unstrapping fuel drums on the ice shelf under a blazing midnight sun and rich blue sky. Relief is finally upon us.

- The fuel dumps bury in a matter of months. Each drum has to be broken out of the ice around it …

- .. and craned onto a new dump site. In 4 months, these will be moved again, constantly upwards.

Every year around about Christmas, the RRS Ernest Shackleton arrives bearing gifts to the tune of a year of fuel, food, science equipment, and about 30 more summer staff which we trade for the outgoing cargo in the form of waste, empty fuel drums, and science samples that have accumulated over the year. November and December saw a huge change around the base as flights were arriving every week bringing some fresh food and some new faces, and warming temperatures saw more of the large vehicles out and about, but this influx of people and cargo right at the end of December has completely transformed the base.

Vehicle line set up to drag the 150 ton garage out of the wind scoop that has formed throughout the year. Two bulldozers, achored to two John Deeres, anchored to two nodwell cranes.

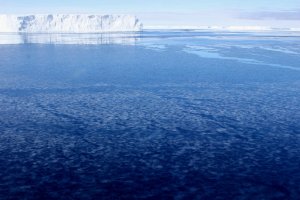

The immediate challenge of relief is moving literally tonnes of food, tens of tonnes of cargo, and hundreds of tonnes of fuel off the ship, onto the sea ice, to then be transported across the sea ice onto the edge of the ice shelf, and then taken across 35km of ice to reach Halley. Then, all this has to be unloaded and stored for the year ahead. The huge operation was carried out under the watchful eye of the Brunt Ice Shelf’s finest disciplinarians: the adelies.

Throughout relief, some rogue penguins waddled up to Halley from their usual hangout on the sea ice, most likely following the drum and flag line that connects Halley to the ship mooring site. Unlike the calm and regal emperor penguins, the adelies are the younger sibling of the penguin family (sorry Bethany!); short, loud, nosey and confrontational. And just about the clumsiest things to ever walk on land. They aren’t half wonderful creatures.

Due to the Antarctic calendar and the planned arrival of the ship in late December, Christmas and New Year’s Eve are fairly subdued affairs as they are expected to be spent unloading the ship; the main celebration in Antarctica is the absolute circus that is Midwinter’s Day on June 21st, which I realise I still haven’t written about but bear with me. The Shackleton was expected to arrive on December 23rd this year so on the 20th in advance we had a fantastic Christmas meal but otherwise my day was spent building an igloo and eventually succumbing to an ‘over-consumption-of-turkey-nap’. As it turns out, the ship didn’t break through the ice until the 28th so the 25th itself turned out to be less busy than anticipated which was a pleasant surprise.

The out-going winterers traditionally have a dinner on the Shackleton after relief is over. For the 8 of us that are left, this was our first time in a year drinking milk, having fresh vegetables, and eggs that aren’t scrambled and then frozen. We had some further excitment on departing the ship to head back to Halley as the mooring ice broke apart just as we were about to leave, meaning that the ship had to ram the ice to establish a new clean edge. When this proved a longer task than expected, we were simply craned onto the sea ice instead!

- On the man-crane!

- Our ride back to Halley

After the ship departs, it visits some of the other British bases on Bird Island, Signy Island and South Georgia before returning to the Falklands. From there, it then ventures back to Halley one last time in late February to take out everyone bar those staying for winter. Thus the ship arriving at Halley for so long has been synonymous with the end of our tenancy here; despite still having several weeks to go before we’ll board the ship for good, those of us that spent winter here are now on the home straight, and recent talk has often been about home.

Those weeks specifically for me, will be spent training my replacement and handing over, finishing any studies and sample collection for the year and mentally preparing to head back into society. As far as the big picture goes before the ship leaves for good, Halley itself needs to be raised as do all of the ancillary science buildings, the cargo needs to be sorted through and distributed and the final repairs from the power down need to be made on the modules. Since the power down and loss of base infrastructure back in July, throughout the following months until now we’ve slowly recovered the likes of lighting, heating, some science experiments, power to the kitchen and more recently, the showers and washing machines. Within a month, the base should in theory be entirely operational again, and ready to withstand another Antarctic winter.

The power down is another thing I realise that I still haven’t written about and to be honest, I find it hard with where to start regarding this so I’ll say this and leave it there. It was such a shit-storm of an event and has caused this year to be referred to by some as among the most difficult Halley winters. Looking back, it’s hard to remember how we actually got through it and there are many mixed emotions surrounding it. I guess that the worst of these was the bitter fatigue of days and weeks with virtually no sleep while fire-fighting problems in a base that was mostly unlit and without heating. In winter darkness, the temperatures fell to -30C on the inside and -55C on the outside. We knew as well that unless we got the generator coolant system working, we would be spending the next 3 months in tents until we could be rescued, in the sad shadow of a frozen base. Having said that, the camaraderie and ‘Bollocks to the world – we can do this’ attitude that manifested itself in this group is something I’m honoured to have shared in. The endless, stoic work to keep the base alive and the unity and cohesion between every one of us is the only reason that we made it through unscathed. The sucker punch thought of facing 3 months in the darkness, in the most inhospitable environment on Earth in a tent was only matched by the cautious optimism in the weeks that followed that we may see this out without jumping ship. Now here I sit in a warm office, with all my science instruments chirping away and having showered 20 minutes ago, wondering how the year would have been different if we hadn’t gone through it. At the very least I’d probably have fewer beer-earning stories to tell in the pub at home.

To avoid leaving this on any sort of sombre note, I was blessed enough to go flying just before the ship arrived! Our winter field assistant was due to head into the field with some recently arrived BAS scientists to collect samples of bird poo (yes, bird poo!). Amazingly, in terms of Antarctic ice movement, one of the best ways to determine how long nunataks and mountain tops that poke through the ice have actually been poking through the ice is by dating the bird droppings on them, as when they are covered in ice there will obviously be no accumulation of poo! Anyway, this trip to the field site required 5 ferry flights worth of fuel, science instruments/cargo, tents and safety gear, and as the pilot of the Twin Otter needs a co-pilot, I, along with a few others, was lucky enough to draw the long straw and fly off base onto the continent to drop off supplies.

- The BAS Twin Otter aircraft

- Loading in ski-doos and sledges

- Airborne!

- Such amazing features. All perspective lost

The weather was fantastic for the entire time with the exception of when we had to land, unload and take off! So while I was assured by the other co-pilots who had later flights that the views of the nunataks and mountains were spectacular, bearing in mind that this is the first time to see terra firma in a year, this was the vista that we were greeted with when we landed.

On the run in though I did get a quick glimpse, so not all was lost.

- Few clouds – nunataks in the distance

- Terra firma!

- Going under a weather front …

- under the front …

- Snow in the distance

Still, I got to take the controls for a portion of the flight and keep the plane level, and it was amazing to see the Hinge Zone and other wildly crevassed areas from the flying altitude of 8000ft. There is no sense of scale looking down at the features, and it’s quite humbling to imagine the likes of Scott and Amundsen and other early Antarctic explorers finding their way across such terrain without modern day climbing and navigation equipment.

- The view on take off – flying purely on instruments

- Emerged from the clouds, amazing view!